Introduction

The promise of work has long been tied to stability. For centuries, the social contract implied that labor, exchanged for wages, secured not only income but identity, belonging, and future. Factories, offices, schools, hospitals—these were not merely sites of production but anchors of life. Yet automation has been loosening these anchors for decades, and today the tide is stronger than ever. Machines are no longer confined to assembly lines; algorithms analyze, predict, decide. Artificial intelligence drafts legal documents, diagnoses illness, writes code, and paints canvases. Robots assemble cars, deliver packages, and prepare meals. Automation does not only transform work—it transforms the idea of work itself, dismantling stability once taken for granted. To understand the modern economy, one must confront how machines are rewriting the social contract of labor, security, and dignity.

A Long History of Displacement

Automation is not new. The Luddites of early 19th-century England smashed textile machines that threatened livelihoods. Every industrial revolution has brought fears of displacement: weaving looms, steam engines, assembly lines, computers. Each wave eliminated jobs but created others, fueling narratives of resilience. Economists insisted new industries would replace old, workers could reskill, societies would adapt. And for a time, they were right. Farmers became factory workers, factory workers became office workers, office workers became service providers. Stability was shaken but restored through adaptation. What makes the present wave different is scope, speed, and scale. Machines are no longer replacing tasks alone; they are competing across domains once thought exclusively human: judgment, creativity, empathy. The displacement is not temporary disruption but systemic transformation.

From Blue Collar to White Collar

Early automation struck hardest at blue-collar labor. Factory robots replaced assembly-line workers, ATMs reduced bank tellers, self-checkout machines replaced cashiers. Yet white-collar workers assumed safety, confident that intellect, analysis, and creativity were beyond machine reach. That confidence has collapsed. Algorithms now perform legal discovery, financial trading, insurance underwriting. AI drafts press releases, generates code, produces artwork. Professionals once insulated by education discover vulnerability: radiologists compete with diagnostic AI, journalists with automated reporting, designers with generative platforms. Automation no longer distinguishes collar colors; it penetrates across spectrum, rendering stability fragile everywhere.

The Illusion of Reskilling

Governments and corporations reassure workers with reskilling promises: learn new skills, adapt, move into industries machines cannot touch. But reskilling rhetoric often masks reality. Training programs exist but rarely match displaced workers to equivalent wages or stability. A factory worker in Detroit cannot become AI engineer overnight; a cashier in Manila cannot transform into data analyst through short course. Structural gaps persist: not all can reskill, not all industries expand, not all opportunities distribute equally. Reskilling becomes mantra, shifting burden onto individuals, absolving systems of responsibility. The illusion sustains hope while systemic displacement accelerates.

Automation and Inequality

Automation amplifies inequality. High-skilled workers in technology thrive, while low-skilled workers face displacement. Capital owners reap rewards as machines multiply productivity, while wages stagnate. Wealth concentrates as labor share shrinks, intensifying divides. Regions dependent on routine work collapse as industries automate, while hubs of innovation concentrate prosperity. Global inequality widens too: wealthy nations adopt automation rapidly, while poorer ones lose comparative advantages in cheap labor. Automation does not distribute evenly; it entrenches hierarchies. The result is dual economy: privileged few harness machines, while many endure instability. Stability once promised to all fragments into privilege for some.

The Psychological Fallout

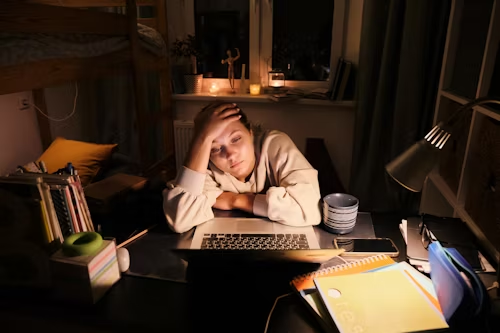

Work is not only economic but existential. Jobs structure days, identities, purposes. Automation erodes not only wages but meaning. Displaced workers report depression, anxiety, loss of dignity. Even those employed fear replacement, living in constant precarity. The psychological fallout is profound: humans built for belonging feel disposable, their contributions undervalued. Societies built on work ethic face crises of identity as machines outperform. Stability once found in routine dissolves into uncertainty, leaving individuals adrift in economies that prize efficiency over humanity.

Stories from the Transition

Consider Omar, a warehouse worker in Morocco replaced by automated systems, now struggling to support family with informal jobs. Or Clara, a journalist in Spain whose newsroom introduced AI-generated reporting, leaving her scrambling for freelance gigs. Or Ravi, a call center agent in India replaced by chatbots, retrained as online tutor earning half his previous income. Or Linda, a radiologist in the United States unsettled by AI tools reading scans faster than she can. Their stories illustrate automation not as abstract trend but lived disruption. Stability unravels in ordinary lives, dreams deferred, futures uncertain.

Global South and the Automation Trap

Developing nations face distinct challenges. Their comparative advantage has long been cheap labor—factories, call centers, outsourced services. Automation threatens to undercut this model, eliminating jobs before alternatives emerge. Millions risk displacement without safety nets. Governments promise digital transformations, but infrastructures lag. The Global South faces automation trap: losing opportunities before reaping benefits, trapped between fading old industries and inaccessible new ones. Inequality between nations deepens, with automation accelerating global divides.

The Politics of Automation

Automation is not inevitable force; it is political choice. Corporations decide to adopt technologies, governments decide to regulate or subsidize, societies decide to prioritize efficiency or employment. Yet rhetoric of inevitability masks these choices, presenting automation as unstoppable tide. This absolves leaders of responsibility, framing displacement as natural law rather than design. Politics of automation reveal power: whose interests are prioritized, whose voices ignored, whose futures sacrificed. The social contract erodes because choices prioritize capital over labor, efficiency over stability, profit over dignity.

The Cultural Shift

Cultures built on work ethic struggle to adapt. Societies valorize employment as measure of worth, stigmatize joblessness, equate labor with identity. Automation disrupts these cultural anchors, leaving voids. What does dignity mean without stable work? What defines adulthood without career? What sustains identity without profession? Automation challenges cultural scripts, forcing redefinition of meaning. Some embrace alternatives—creative pursuits, community work, leisure—but cultures lag, still measuring worth by jobs that machines now perform. Cultural lag intensifies crises, leaving individuals unmoored in societies clinging to outdated metrics.

The Social Contract in Crisis

The social contract once tied work to security: labor provided wages, benefits, retirement, belonging. Automation erodes each link. Wages shrink as machines replace labor, benefits vanish with gig work, retirement falters with instability, belonging dissolves in fragmented jobs. The contract unravels, leaving workers exposed. Governments scramble with welfare patches, corporations deflect responsibility, individuals absorb shocks. The crisis is not technological but social: systems fail to update contracts for realities of automation. Without reimagined contract, instability becomes permanent condition, dignity fragile, futures precarious.

Resistance and Adaptation

Resistance emerges. Workers organize against automation layoffs, communities demand protections, activists call for universal basic income. Some governments experiment with shorter workweeks, job guarantees, retraining with support. Cooperatives explore human-centered models, prioritizing dignity over efficiency. Adaptation is uneven but growing, fueled by recognition that automation is not neutral. Resistance reframes automation from inevitability to negotiable, demanding balance between efficiency and humanity. Yet opposition faces immense forces: corporate lobbies, political inertia, cultural myths. Whether resistance expands or falters will shape future of work.

The Future Beyond Work?

Some envision world beyond work, where automation liberates humans from drudgery. Universal incomes, automation dividends, community labor could sustain lives, freeing people for creativity, care, exploration. Yet such futures remain speculative, resisted by elites profiting from hoarding gains. Automation’s potential to liberate exists, but current trajectory exploits rather than emancipates. Future beyond work requires political courage, cultural imagination, and structural change. Without it, automation will not free but fracture, leaving societies defined by instability rather than liberation.

Conclusion

Automation is rewriting the social contract. It dismantles stability, displaces livelihoods, amplifies inequality, corrodes meaning. Machines promise efficiency but deliver precarity when systems prioritize profit over people. To see automation clearly is to see choices: whose futures matter, whose dignity counts, whose labor endures. The end of stable jobs is not inevitable destiny but political design. To reclaim stability requires new contract—built not on outdated promises but on recognition that humanity deserves more than disposability in age of machines. Until then, automation will continue to erode stability, rewriting futures not in ink but in code, indifferent to human need unless humans demand otherwise.